In a CBC interview, Peter Mansbridge asked Marie Henein two interesting questions. First, is this case, this type of crime, distinctive? Second, is the system broken? [1]

Henein answered “no” to both questions, as one would expect given her class position.

The questions themselves were interesting, though, especially the second one. Is the system broken? This is a more complex question than one might think.

Sexual assault cases have at least three issues that make them distinctive which Henein ignored.

First, sexual assault is a highly gendered act terms of who is most likely to commit it and against whom.

Second, sexual assault against women has been poorly understood and not taken seriously enough, by the state, other social authorities, and most people.

Third, sexual assault is unusual in the degree to which it traumatizes the victim, brings shame on the victim, and violates the personhood of the victim.

In sum, sexual assault is not only gendered but gendering: its most common forms contribute to the unequal power relations which produce men’s and women’s differential social identities.

Hence the stakes of the trial. Many feminists, myself included, hoped that the court’s decision would help undermine the relative impunity of men to commit sexual violence against women, and thereby help equalize the power relations between men and women. Sadly, this did not happen.

Does this indicate that the system is broken?

The notion of ‘broken’ implies a teleology of design and function. Thinking this way is an anthropocentric mistake. Social institutions are rarely the products of intentional design and as such have no ‘proper functions’. Rather, they emerge from processes of evolution. They do not function or malfunction; they adapt or maladapt.

The criminal justice system evolved as an aspect of state sovereignty, specifically as a sink for conflicts between the sovereign and its subjects.

Consider the logic of a criminal trial, which takes the form of a ritual symbolic combat between the sovereign and the defendant, a combat from which the sovereign must emerge victorious whatever the verdict.

In a criminal trial, there is an injury, and an injured party. However, the injured party is not the actual victim of the crime, and the injury is not the actual harm done to that person.

Rather, the injured party is the sovereign, and the harm done by crime which the courts work to repair is the violation of the sovereign’s authority. What matters most is that someone may have broken the law; any harm to the complainant is secondary at best.

So the courts are not presently adapted to address issues of social justice, equity, or equality, nor to repair the harm done to the immediate victims of crimes. They are adapted to restore the authority of the sovereign which has been damaged by the occurrence of a criminal act.

However, in a putatively democratic society, sovereignty is supposed to reside with the people, not with the head of state, the elected government, or even the state bureaucracy.

This supposition implies that women complainants who testify against an abuser are entitled to a justice, though not as human beings who have been injured, but as members of the sovereign body of citizens.

Constatively speaking, however, neither the democratic quality of the polity nor the citizenship of women are givens. Both of these things are continually established or eroded through trials of strength among various social actors.[2]

As with any social group, women’s citizenship depends on the extent to which their rights as citizens are effectively protected. To the extent that women’s rights are protected less effectively than men’s, women lose their citizenship and become the collective property of all men or even the individual property of specific men.

Establishing social equality is, at the very best, a secondary adaptation of the courts. Their primary adaptation is to resolving challenges to state sovereignty.

Did the courts fail? The answer is bound to be a bit tautological. Whether the courts failed depends on the extent to which women are citizens. But court’s decision itself affects this extent.

To put it another way, the courts only failed if one expects them to be something beyond what they actually are, if one expects — or demands — sovereignty to be more than it already actually is.

What is the upshot of all of this? I’m hesitant to comment directly because I’m not a woman and I’ve not experienced sexual assault.

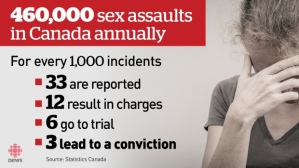

However, this analysis implies that the courts simply cannot meet the needs of women as particular, embodied subjects — as wounded, grieving subjects, as bodies and souls in pain. The courts will always fail on that level, which is probably why so many women refrain from prosecuting the men who violate them. At most, the courts can perhaps meet the needs of women as universal subjects, as citizens. The stakes of a court case — the stakes which the courts are at least somewhat equipped to handle, that is — are public, not personal.

But this is unsatisfying. The body in pain, the wounded soul, is not simply a private matter. It is a social issue. The pain of women who have been sexually violated is a pain caused by men’s historical impunity to sexually violate women. Institutions designed to deal with subjects only in the abstract are inadequate to address the needs of the vulnerable and the oppressed. Actual equality requires deeper changes to our institutions than have yet been achieved.

[1] Postscript, Nov 2016: Now that Henein is back in the news, I’d like to add a couple of notes about things which I took for granted as obvious when I wrote this piece, but which not everyone might think are obvious (or not everyone might think I think are obvious). First, it seems pretty obvious that Ghomeshi did the things he was accused of doing, whether or not they meet the legal definition of sexual assault. Second, it should be obvious that Ghomeshi was entitled to a legal defense, and that in providing him with an aggressive defense Henein was simply doing her job to the best of her ability. Third, I’m not a legal scholar but it seems probable that the judge’s ruling was consistent with established legal norms given the nature of the evidence for the prosecution. Where does that leave us? A bad thing happened, the criminal justice system functioned normally, and social justice was not served. In situations like this, personal criticism of the individuals involved is not so helpful. We need systemic critique, which is what I’ve tried to develop in this post.

[2] This is true of men as well. In principle all accused are entitled, as citizens, to a legal defense, the presumption of innocence, due process, and so on. In practice, Ghomeshi could secure the effective exercise of these entitlements not only through his gender privilege (in which his presumed sexual entitlements as a man coincided with his entitlement to presumption of innocence as a citizen) but also through his class position, because he could hire skilful legal representation. Without the latter, the former might not have been enough.

Great thoughts. love, dad

LikeLike

“Many feminists, myself included, hoped that the court’s decision would help undermine the relative impunity of men to commit sexual violence against women, and thereby help equalize the power relations between men and women. Sadly, this did not happen.”

In short, many feminists think that:

a) The accusation, and any other like it, is to be taken as true on a priori grounds, and should automatically result in a conviction once made, Believe all survivors, etc. Alternately:

b) A guilty verdict would have been congenial to the ends of the equalist agenda, and thus would have been a boon, whether or not the guy was, like, actually guilty of anything. The good of the many outweighs the good of the few or of the one, and like that.

We actually get a pretty good deal out of State sovereignty where justice is concerned in that, in the criminal or other legal trial, the State cannot show favoritism to one party or another (as Hobbes said, all social distinctions between citizens must be made to vanish before the Sovereign), pander to this or that political agenda, and different things like that without seriously compromising the sovereignty- a fortiori, the very legitimacy- of the State. The State therefore has a mighty incentive, by way of a foundational and indelible power-interest, in keeping lawless social forces such as the irrational passions of the mob, or frivolous and irresponsible academic fads and fashions of the moment, strictly out of the justice process (as it did in the Ghomeshi case). This is a structural constraint that won’t change even if the SJWs do seize control of the State apparatus, since the rest of their ambitions absolutely presume a sovereign State capable of enforcing them and otherwise imposing the Cathedral’s ultraminoritarian will on the ever-increasingly resistant broad popular masses. It follows that the hoped-for Feminist/SJW paradise can’t be realized in this life and won’t be, since fickle sentiment and fancy must yield to the gravitas of the Law in its majestic continuity

LikeLike

Dear Dissenting Sociologist,

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment on my post. I certainly will think carefully about the theses you’ve presented in your comment. However, it seems to me that we do not share enough premises in common to be able to hold a constructive discussion at this time.

Best wishes,

Chris

LikeLike

I am sure that you Brahmins have attained to especially exalted heights of consciousness, and on an esoteric basis possess conceptions of justice so enlightened that they must never be taught to the profane and mere once-born masses, and in any case cannot be grasped in such limited and plebeian terms as “Sovereignty”, “the rule of law”, the so-called “importance of procedure in the criminal trial”, “equality before the law”, and other vulgar fallacies deployed by sweaty insolent working-class men to oppress upper-class White women and other disadvantaged groups. Forgive me for having presumed to speak without first being spoken to; I understand that, in a caste or other patriarchal hierarchy of learneds, a Brahmin who condescends to debate a social inferior disgraces himself in a socially very serious way. Some undergraduate Red Guard finds out you’ve been talking to a cracker online and then, whoops- there goes your tenure! But I’m sure the hoi polloi love and respect you and the rest of their rightful superiors in your lofty dignity, and that their feelings towards you all will never boil over into, say, a populist revolt led by a celebrity demagogue or anything like that. Have a good one…

LikeLike

Hang on … K, is that you? What’s with the name change, the anonymity? More to the point, what’s with the Manosphere dog-whistle lingo (equalist agenda? SJWs?) and the straw man fallacy?

LikeLike